++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

The first time I ever heard anyone talk about feelings was after my 29th birthday when I entered a seven week in-patient treatment program for alcoholism and addiction in 1980. I intellectually understood what the word ‘feelings’ meant, but I had no personal idea what a feeling even was.

The therapists soon realized this, and worked with me through practice sessions so I could begin to learn to identify feelings in my body. They had me sit in a chair and then had me focus and pay attention to the feeling of my feet on the floor, of my butt on the chair, of my hands resting on my knees. “Now shift your weight in your chair and see if anything feels different.”

I felt like a girl version of the wooden puppet Pinocchio. Not only was I unable to feel a SELF inside my body, my SELF could not feel itself inside of my body, either. It took me many years before I could experience my own life in any kind of a feeling way. After that there were many times when I wished I had never begun that journey. Feelings, well, they FEEL.

I was nearly constantly overwhelmed with the feelings of trauma throughout the entire 18 years of childhood with my mother. Positive feelings were forbidden. Once, as an adult, I began to feel, I found (as I now understand far more completely) I could not regulate them. I could not alter their intensity, and once I was in their grip I could not get out of it.

I now understand that the unsafe and insecure infant-childhood I had changed the way my right limbic emotional brain processes emotion — period. I did not learn to self-soothe. I did not learn how to smoothly and easily shift gears between feeling states. In fact, as I mentioned, I did not even know what a feeling really even was.

++++

I mention this today because I am going to present two pictures here from Dr. Dacher Keltner’s chapter on compassion (from his book Born to Be Good: The Science of a Meaningful Life) along with a bit of the text he includes with them.

The exercise I suggest is for readers to just spend a little time looking at first one of these pictures and then at the other. I find it fascinating that I can fully feel the difference IN MY BODY between how my body feels, and therefore how I feel, in response to each of these pictures.

The feeling shift in my torso involves my breathing. As I mentioned in yesterday’s post, we can become mindfully aware of our experience of breathing as we shift from automatic pilot breathing to breathing with our SELF-conscious awareness. These two pictures, to one degree or another, offer an example of how breathing and mindful awareness are connected together.

++++

Picture number one:

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

I realize the quality of the pictures is pretty shabby, but they still work just fine to demonstrate how our vagus nerve system responds within our body differently as we experience emotion and feeling.

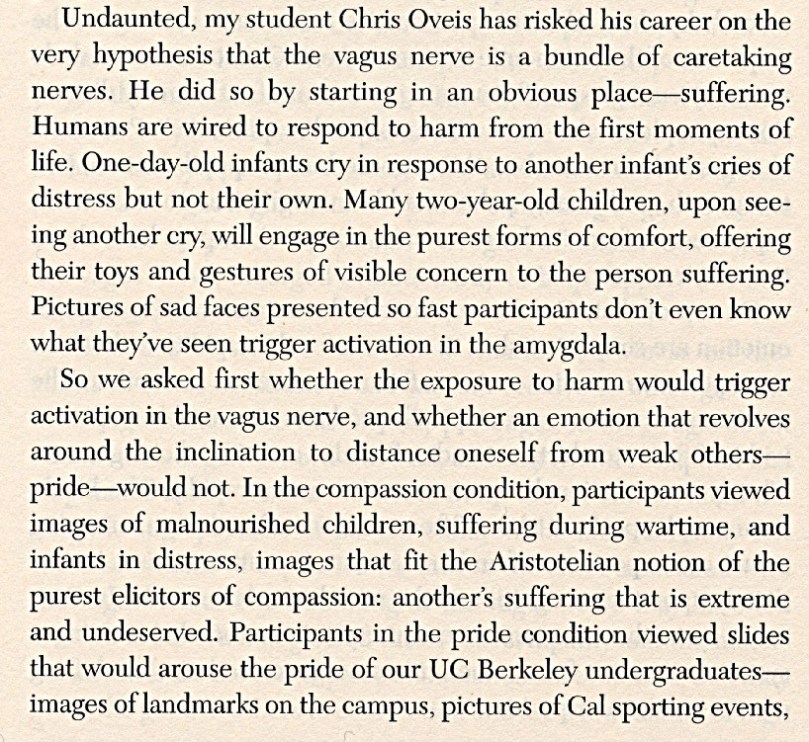

I am posting again today Keltner’s writing about how these photographs were used in research, which is part of the whole chapter on compassion that I posted the other day that includes some writing on altruism.

I just wanted to mention today that in cases of severely abusive parents something is obviously terribly wrong with their compassion-altruism-be good spectrum of response. Research, as I’ve mentioned previously, about Borderlines shows that their vagus nerve system does not operate in a normal way.

Keltner states here:

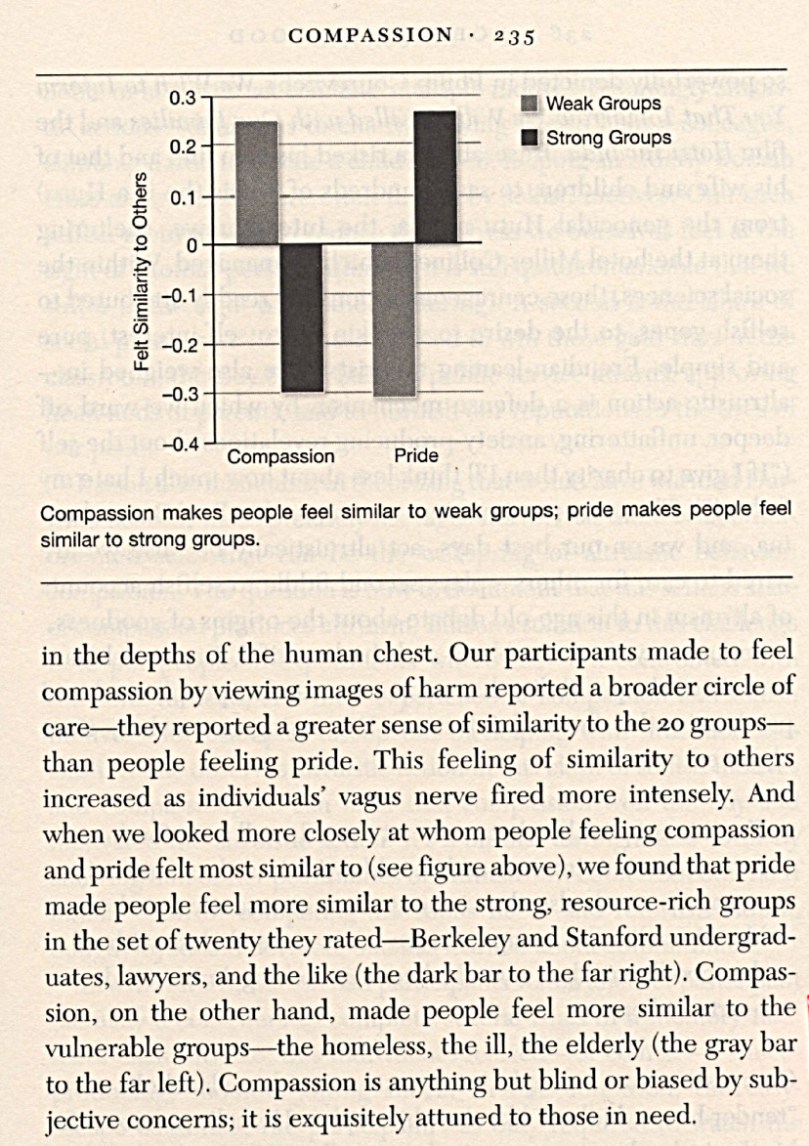

“With increasing vagus nerve response, participants’ orientation shifted toward one of care rather than attention to what is strong about the self.” (page 234)

I am reminded of my thinking about my mother’s distorted self, about her distorted relationship with this distorted self, and about her distorted relationship with everyone in her universe, most specifically with me.

In her relationship with me my mother was solely occupied with what she unconsciously perceived as being WRONG with herself as she projected ALL of that wrongness onto me — and then punished me for it.

By taking what was WRONG with herself and placing it all on me, she was making her good self STRONGER in some bizarre and distorted way. But she couldn’t even just do this half of her psychosis without doing the other half, which was to ‘personify’ her projection of goodness onto my younger sister as she made her the all-good child in a similar way that she made me the all-bad one.

While Keltner is obviously not talking about child abuse in his writings, there is no way that I can avoid the fact that it is within this same vagus nerve system that these distorted patterns — of ‘strong’ versus ‘weak’, of what ‘belonged’ and what did ‘not belong’ within my mother’s version of herself, along with who she identified with and who she refused to identify with (as being weak versus strong) — operated within my mother.

My mother lacked any normal self-reference point within herself that is necessary for the normal demonstration of the reactions that Keltner describes in this research (see below). Because she did not have any true sense of what was strong about herself, she could not be mindful of the fact that her entire psychic, mental system — and the behavior that was its result — operated through externalized inner dramas that she acted-out, outside of her self as they mostly involved tortured, battered, hated, shunned, and terribly abused ME.

++++

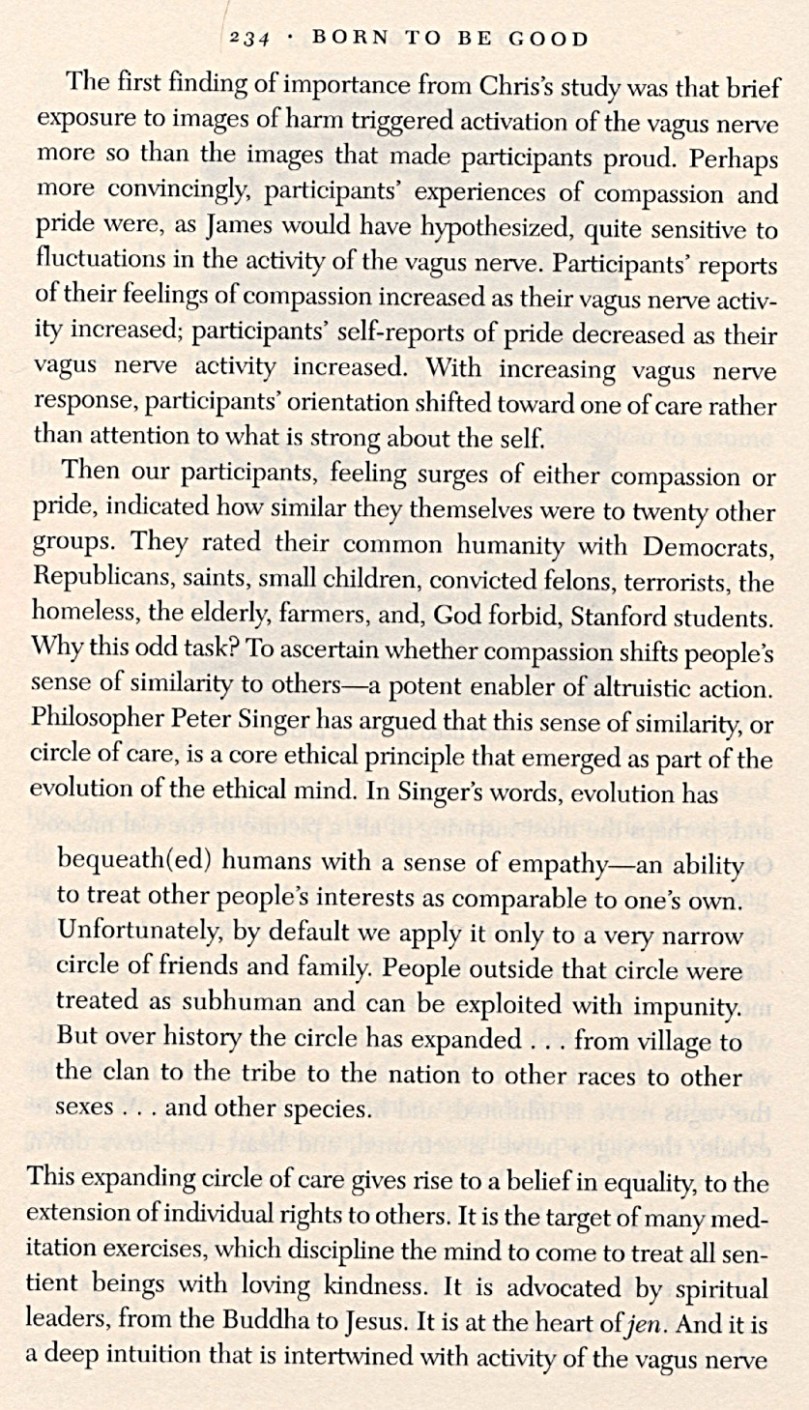

Although the research presented here had nothing overtly to do with infant-child abuse or about a comparison of safe and secure attachment versus unsafe and insecure attachment, I believe absolutely that this research model could be used in combination with these factors.

What would be discovered would be the deeper levels of how shifts between so-called pride and compassion are actually showing the strength or weakness of the SELF. The weaker and more unsafely and insecurely attached a self is in the world, the more distorted their vagus nerve reaction is likely to be on this pride-compassion spectrum.

But what might register in such a study as a tendency toward pride is actually a tendency to NOT be able to recognize any weakness within the self at all. Such a person learned (it was built into their body-brain) that weakness meant threat of death. If the early trauma could not be avoided in any other way, the body-brain simply shuts off any ability to recognize self-weakness at all. Awareness of weakness costs too much — as does weakness itself.

++++

In my thinking, I suspect that the stronger a self REALLY is, the more fluidly that self will be able to afford the cost of recognizing weakness in others. They can afford to allow themselves to resonate with need and weakness through the feeling of compassion. They will also be able to afford to respond with care.

If a self is REALLY weak rather than strong, they cannot afford to identify with another’s weakness. It simply costs too much. “I am strong enough to survive so I can afford to help others to survive” is an entirely different mantra than “I know I am vulnerable and weak (though I can’t even afford to let myself know this) so I must align myself with the strongest (and act like I am one of the strongest) to survive. I cannot afford to give anything to anyone else.”

My mother took all this weakness to another level that made her an extremely dangerous mother. Not only could she not be consciously and mindfully aware of her own weaknesses and vulnerabilities of her own self, she was hell bent on actively destroying her own projected version of weakness — again, of course, ME. Not only could she not appropriately care for me, or have compassion for me, she attacked me as she tried to destroy me. It would not surprise me if these dynamics operate on some level for all severely abusive parents.

If this is true, then abusive parents have the weakest selves possible.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

The part of Keltner’s next cited above related to this particular research:

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++